The reality is relatively simple even though the appearance is complicated and confusing. What are we talking about?

- Wars that are hugely profitable for a few individuals and businesses

- Unauditable Pentagon accounting

- Government debt that will never be repaid

- Levitation of S&P and bond markets

- Gold price suppression

- So much more

We all know “something is wrong” but we keep riding the same corrupt “gravy train” because it works for many powerful people. Consider the interlocking complicity involved in the following:

Iraq and Other Wars

The previous administration produced “evidence” that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction and then claimed it was necessary to invade Iraq, distribute oil contracts to American and British oil companies, initiate “no-bid” contracts to politically connected American military contractors, massively increase government debt, and create huge profits for selected companies and industries. Those profits flowed back to the financial elite, agreeable congressmen, others in government, and to many American workers.

Even though it is now generally agreed that Iraq had no weapons of mass destruction and no means of launching those non-existent weapons against the United States, a great many connected people and businesses benefited financially from the Iraq War. Interlocking complicity worked well to promote the war and to profit from it.

Pentagon Accounting

About 12 years ago, Secretary of Defense, Donald Rumsfeld revealed that $2.3 Trillion was “missing” from the Pentagon books. (“War Racket Update” by acting-man.com – site down temporarily)

“A number of knowledgeable observers admitted that the Pentagon’s ‘books are cooked’ and that in essence, a giant cover-up was going on. A mixture of waste and theft on a truly breathtaking scale was and still is underway.”

It has been my experience that bad or fraudulent accounting is enabled, encouraged, or actively created by management. We can safely assume that the many highly intelligent people who work at the Pentagon could more accurately and transparently manage their operations if they wanted to do so. Hence, fraud and theft exist because management wants it – many people benefit while accountability is neither encouraged nor beneficial to those who are actually in charge. The powers-that-be, congress, the administration, and military contractors are complicit in working the system so that all parties benefit, other people pay the costs, there is minimal accountability, and the necessary payoffs are made. Interlocking complicity works well for those in charge of Pentagon funds and for those receiving the funds.

Government Debt

Congress has not passed a budget in five years and has been deficit spending for decades. The shortfall between revenues and expenses is borrowed with the understanding that the debts will never be paid – just “rolled over.” The financial and political elite benefit, government pays out massive amounts for military contracts, health care, prescription drugs, retirement programs, Social Security payments, Medicare, unemployment, aid to states, and it goes on and on. That explains how the U.S. government is officially in debt over $17 Trillion and has accrued another $100 – $200 Trillion in liabilities that have been promised but are not currently funded. Since most Americans are benefitting from one or more of these government distributions, most Americans are complicit in this giant borrow, spend and print Ponzi scheme. Because so many people benefit, few individuals or businesses want the process materially changed. Of course many people talk about balancing the budget, cutting spending, and fiscal accountability, but it is only talk. Because Congress has been unable to pass a budget in five years and must borrow a $Trillion or so each year there will be no accountability or budget cutting anytime in the near future. Interlocking complicity rules while we ride the giant government gravy train.

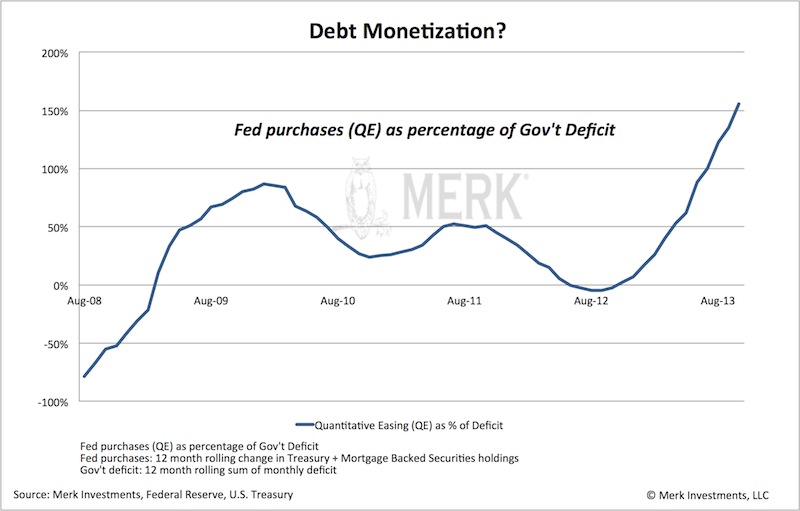

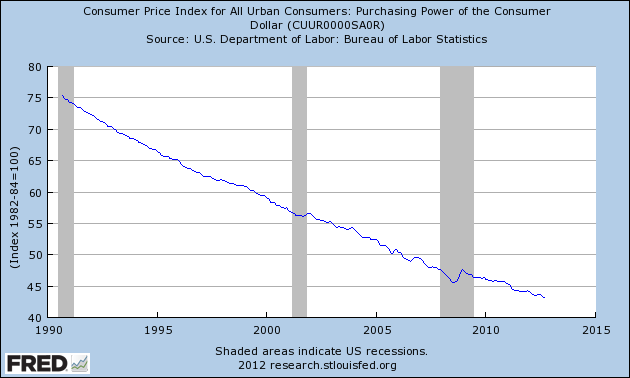

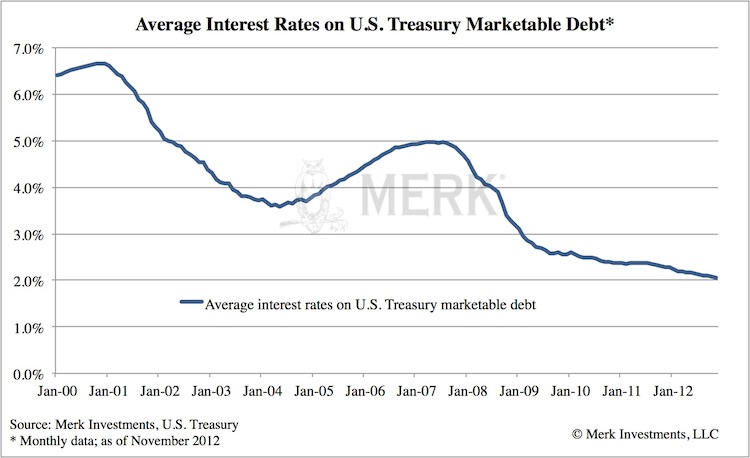

QE and the Levitation of Stock and Bond Markets

Even a quick glance at the last five years of market prices shows that QE has been a huge benefit to the stock and bond markets and that much of the funny money being “created out of thin air” by the Fed finds its way into those markets. Hence the stock and bond markets have been levitated while “main street” and the bottom 90% (those who have little of their net worth in stocks and bonds) have derived minimal or no benefit from QE. However, most of us realize that the US government cannot limit spending to only the revenue it collects, and that QE greatly benefits the financial and political elite. Interlocking complicity dictates that QE will continue as long as possible, even though “printing money” and debasing the currency have never successfully worked throughout history.

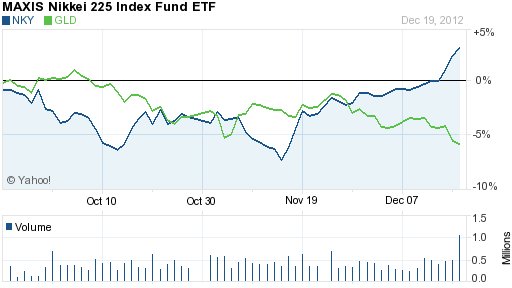

Central Banks and Gold Price Suppression

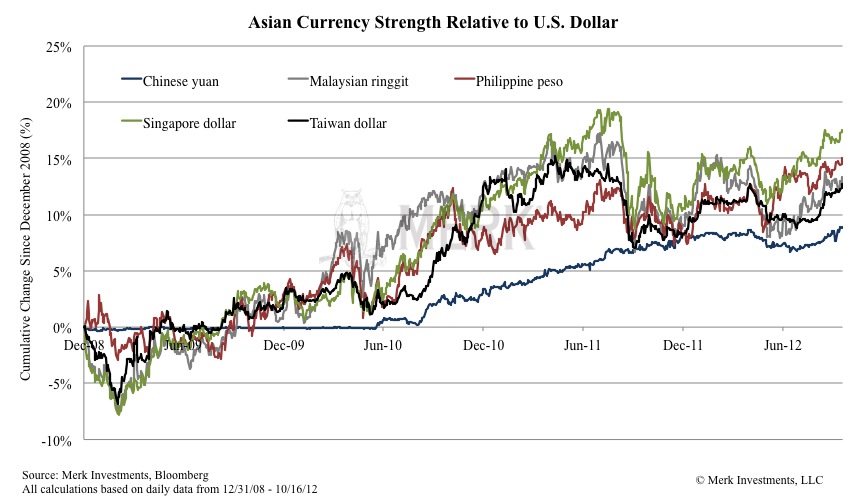

Central Banks (Bank of England, Federal Reserve, ECB) have sold or “leased” gold into the market, via bullion banks, to suppress the price of gold and to promote the idea of Pound, Dollar and Euro strength. Since central banking rules allow them to claim that gold is still their asset, even though it is physically gone, this process can work until the central banks are unwilling or unable to sell or “lease” additional gold. The Chinese, Indians, and Russians have purchased the gold directly from bullion banks, or taken delivery on futures contracts, shipped the gold to Switzerland where it has been melted down into kilo bars, and then moved it to the Eastern countries. A huge amount of gold has left the west where it is undervalued and now is vaulted in the East where it is better appreciated.

During the past several years the Chinese have vastly increased their gold holdings at favorable prices while dumping some of their depreciating dollars. The Western central banks further the illusion of value in unbacked debt based paper money while claiming gold is in a bubble, gold and the gold standard are barbarous relics, and enabling paper currencies to survive for a while longer. Interlocking complicity in the gold leasing and gold price suppression scheme currently benefits both the eastern and western countries.

Summary

The Pentagon cannot account for $Trillions. Since there is little incentive to stop the fraud, waste, and phony accounting, and since there is a large incentive for it to continue, expect the graft, corruption, black budget items, and payoffs to continue. Interlocking complicity works especially well at the Pentagon.

The US government does not want to cut spending and has a limited ability to increase revenues. Expect borrow and spend politics to dominate until a “reset” occurs and then expect a crisis and many speeches from important politicians who just noticed what has been obvious for decades. Interlocking complicity works well for congressional payoffs, reelection speeches, increasing power to the administrative branch, and, of course, massive profits to the industries that benefit the most from deficit spending, such as military contractors, banking, health care, pharmaceuticals and others.

Gold price suppression benefits western governments and central banks while the Chinese and Russians benefit by purchasing valuable gold with increasingly devalued dollars. Expect gold price suppression to continue until the west runs out of gold that can be melted down and shipped east. However, demand for physical gold is quite strong while supply is limited. Expect gold to trade MUCH higher in the next few years.

Interlocking complicity produces a degree of stability as it helps maintain the status quo, which is very important to the powers-that-be. Interlocking complicity ensures that accountability, oversight, and ethical practices are low priorities, while payoffs and no-bid contracts will maintain their important role in government operations. Interlocking complicity ensures that little change will occur until it is forced upon us.

Ask yourself

- Are you prepared for a reset of our financial and social systems?

- The Chinese are trading increasingly less valuable dollars for increasingly more valuable gold and silver. Should you do likewise?

- Can a government spend more than it collects in revenue – forever?

- Debasing the currency has never worked well in the past. Will this time be different for Japan, Europe and the United States?

- Will Wall Street, Congress, military contractors and the pharmaceutical industry lobby for what is good for you or for them?

GE Christenson

aka Deviant Investor

By: GE Christenson

By: GE Christenson

By: Axel Merk, Merk Investments

By: Axel Merk, Merk Investments  Americans need to take a serious look at how the purchasing power of the dollar is being destroyed. Rampant poverty, declining real incomes and higher prices are all the guaranteed results of a Federal Reserve that remains committed to destroying the value of the dollar. A dollar saved today that has less purchasing power a year from now equates to the “silent” destruction of the dollar, an event which has gone virtually unnoticed and unprotested by the American public.

Americans need to take a serious look at how the purchasing power of the dollar is being destroyed. Rampant poverty, declining real incomes and higher prices are all the guaranteed results of a Federal Reserve that remains committed to destroying the value of the dollar. A dollar saved today that has less purchasing power a year from now equates to the “silent” destruction of the dollar, an event which has gone virtually unnoticed and unprotested by the American public.

By

By

Both the Federal Reserve and the Bank of Japan have gone all in with their attempts to revive weak, debt burdened economies with a pledge of unlimited money printing.

Both the Federal Reserve and the Bank of Japan have gone all in with their attempts to revive weak, debt burdened economies with a pledge of unlimited money printing.

By

By