By: Axel Merk, Merk Investments

By: Axel Merk, Merk Investments

Sidetracked by the discussion over the “fiscal cliff” and possibly a New Year’s hangover, it’s time to face 2013 in earnest. Is the yen doomed? Will the euro shine? What about Asian and emerging market currencies? Will gold continue its ascent? And the greenback, will it be in the red?

Before we look too far forward, let’s get some context:

- “Central banks hope for the best, but plan for the worst” was our theme a year ago. With everyone afraid of the fallout from the Eurozone, printing presses in major markets were working overtime. We argued this would benefit currencies of smaller countries – be that the so-called commodity currencies or select Asian currencies – that feel less of a need to “take out insurance.”

- While we were positive on the euro when it approached 1.18 versus the U.S. dollar in 2010, arguing the challenges are serious, but ought to be primarily expressed in the spreads of the Eurozone bond market. Then in the fall of 2011, we grew increasingly cautious because of the lack of process: just as it is difficult to value a company if one doesn’t know what management is up to, it’s difficult to value a currency if policy makers have no plan. In the spring of 2012, when we were most negative about the euro, we lamented the lack of process in a Financial Times column. European Central Bank (ECB) chief Mario Draghi appeared to agree with our concerns, imploring policy makers to define processes, set deadlines, hold people accountable. After his “do whatever it takes” speech in July 2012, he took it upon himself to impose a process on European policy makers in early August 1. We published a piece “Draghi’s genius” where we called for a bottom in the euro. We were inundated with negative feedback in the immediate aftermath of our analysis from professional and retail investors alike, confirming that were not following the herd, nor buying something that’s too expensive.

- While we liked commodity currencies in the first half of the year because of printing presses in larger economies working overtime, we grew a little cautious as the year moved on, partly because of valuations. Each commodity currency has its own set of dynamics, as well as their own Achilles heel: in the case of the Australian dollar, we had some concerns about its two tier domestic economy (not all of Australia was benefiting from the commodity boom), but also about the perceived slowdown in China.

- We studied the Chinese leadership transition with great interest; while 2012 may have been a year in transition, more on the dynamics as we see them play out below.

- Back in the U.S., we squandered another year to get the house in order. The fiscal cliff was a distraction; we need entitlement reform to make deficits sustainable. Europeans have no patent on kicking the can down the road. But unlike Europe, the U.S. has a current account deficit, making it more vulnerable should investors demand more compensation to finance U.S. deficits (that is, higher interest rates).

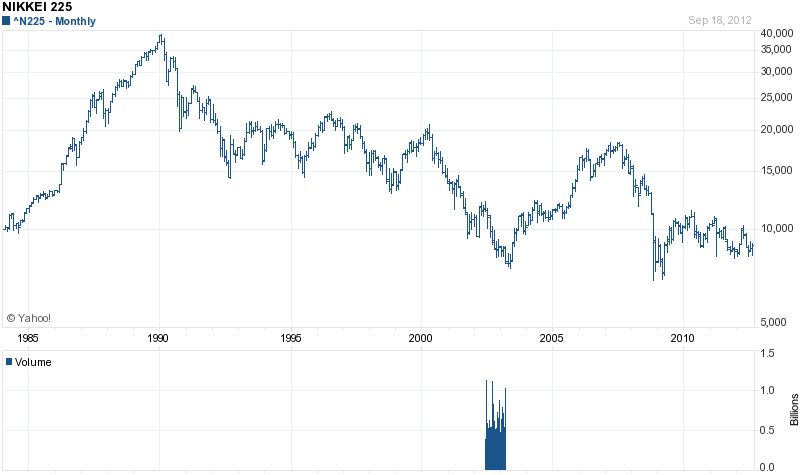

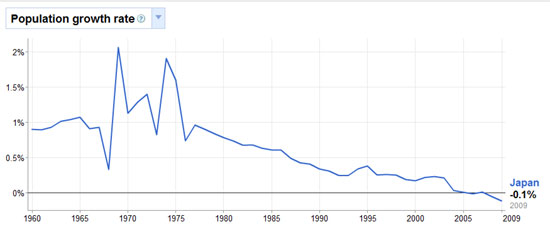

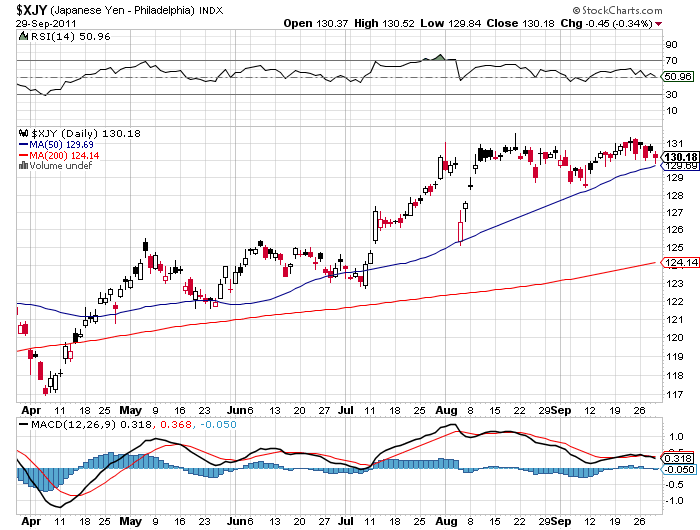

- Japan: the more dysfunctional the Japanese government has been, the less it could spend, the less pressure it could exert on the Bank of Japan. Add to that a current account surplus, and all this “bad news” was good news for the yen. Countries with a current account surplus don’t need inflows from abroad to finance government deficits; as a result, the absence of economic growth that keeps foreign investors away is of no detriment to the currency. Conversely, countries with current account deficits tend to pursue policies fostering economic growth to attract capital from abroad. However, in late 2012, we published a piece “Is the Yen Doomed?” What happened? Japan was about to have a strong government. More in the outlook below.

We believe the currency markets are well suited for decision-making based on macro-analysis. Just as throughout 2012 the themes were evolving, please keep in mind that our 2013 outlook may be outdated the moment it is published, as we update our views based on new information or a new analysis of old information. Still, those who have followed us over the years are well aware that we like to shift our views within a framework. Please consider our 2013 outlook in this context:

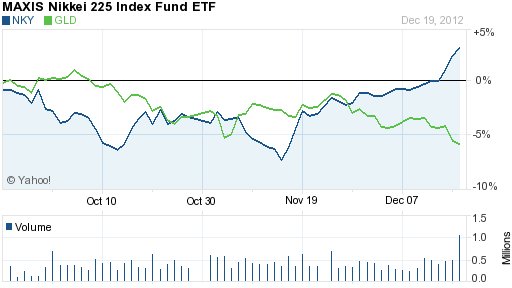

- We believe the yen is indeed doomed. We remove the question mark. Prime Minister Abe’s new government sets the stage, but key to watch are:

- Abe’s government will appoint the three top positions at the Bank of Japan, as the governor and both deputy governors retire. Recent appointees have already been more dovish. Japanese culture is said to prefer talk over action, but the time for dovish talk may finally be over (despite their dovish reputation, the Bank of Japan barely expanded its balance sheet since 2008; in many ways, of the major central banks, only the Reserve Bank of Australia has been more hawkish).

- Japan’s current account is sliding towards a deficit. That means, deficits will start to matter, eventually pushing up the cost of borrowing, making a 200%+ debt-to-GDP ratio unsustainable.

- Abe’s government is as determined as it is blind. Abe believes a major spending program is just what Japan needs. As far as the yen is concerned, Abe may be getting far more than he is bargaining for.

- But isn’t everyone negative on the yen already? Historically, it’s been most painful to short the yen; as such, many have not walked their talk. We expect some fierce rallies in the yen throughout the year. Having said that, the yen looks a lot like Nasdaq in 2000 to us. Not as far as technicals are concerned, but as far as the potential to fall without much reprieve.

- The euro may be the rock star of 2013. Boring is beautiful. Sure, there are plenty of problems, but the euro is morphing into yet another currency, but is still priced as if it had a contagious disease. While the Fed, the Bank of England, the Bank of Japan are all likely to engage in further balance sheet expansion (we refer to it as “printing money” as assets are purchased by central banks, paid for by entries on computer keyboards, creating money out of thin air), there’s a chance the ECB balance sheet may actually shrink. That’s because some banks have indicated they will pay back early part of the €1 trillion in 3-year loans taken from the ECB. Some suggest the ECB might print a boatload of money should the “Outright Monetary Transaction” (OMT) program be activated to buy the debt of peripheral Eurozone countries. Keep in mind that the OMT program would be sterilized, likely by offering interest on deposits at the ECB. As such, the OMT would lower spreads in the Eurozone and, through that, act as a massive stimulus. In our assessment, however, such a stimulus is far less inflationary than central bank action in other regions. It’s no longer a taboo to be positive on the euro, but most we talk to are at best “closet bulls.”

- The British pound sterling. The Brits are getting a new governor at the Bank of England (BoE) in the summer, the current head of the Bank of Canada (BoC), Carney. One of the first speeches Carney gave after his appointment was made public was about nominal GDP targeting. Carney will have a chance to replace many of the current BoE board members. That’s the good news, as the old men’s club is in need of a makeover. The not-so-good news is for the sterling. British 10 year borrowing costs have just crossed above those of France. We’ll monitor this closely.

- As the head of the BoC, Carney was particularly apt at talking down the Loonie, the Canadian dollar, whenever it appeared to strengthen. If Macklem, his current deputy, is appointed, we may get a real hawk at the helm of the BoC. We are positive on the Loonie heading into 2013, but will monitor developments closely, as there are economic cross-currents that, for now, Canada appears to be handling very well.

- Staying with commodity currencies, we are cautiously optimistic on the Australian dollar (China better than expected; monetary policy more hawkish than priced in) and New Zealand dollar (more hawkish monetary policy on better than expected growth). We continue to stay away from the Brazilean real and leave it for masochistic speculators looking for excitement.

- We are positive on Norway’s currency (joining the above mentioned rock star, with greater volatility), yet cautious on Sweden’s (priced to perfection is not ideal when things are not perfect, even in Sweden).

- China: the new leadership has indicated that liquidity for the Chinese yuan may be their top currency priority. That’s great news, as we believe it implies policies that attract investment, not just from the outside, but also with regard to a development of a more vibrant domestic fixed income market. We are more positive on China than many; more on that, in an upcoming newsletter (click to sign up to receive Merk Insights)

- Korea, Malaysia, Taiwan: all positive, benefiting from both internal forces, but also beneficiaries of actions in other large economies. If we have to pick a favorite today, it would be Korea, but keep in mind that the Korean won is the most volatile of these currencies.

- Singapore: we continue to like the Singapore dollar. A year ago, we started using it as a substitute for the euro (rather than using the U.S. dollar as the safe haven currency). The currency may well lag the euro’s rise, but the lower risk profile of the currency makes it a potentially valuable component in a diversified basket of currencies.

- Gold. We expect the volatility in gold to be elevated in 2013, but consider it good news, as it keeps the momentum players at bay. We own gold not for the crisis of 2008, not for the potential contagion from Europe, but because there is too much debt in the world. We think inflation is likely a key component of how developed countries will try to deal with their massive debt burdens, even as cultural differences will make dynamics play out rather differently in different countries. Please see merkinvestments.com/gold for more in-depth discussion on our outlook on gold.

And what about the U.S. dollar? While much of the discussion above is relative to the U.S dollar, the greenback itself warrants its own analysis:

- Investors in the U.S. should fear growth. The spring of 2012 saw the bond market sell off rather sharply as a couple of economic indicators in a row came out positively. Bernanke wants to keep the cost of borrowing low, but can only control the yield curve so much. That’s why, in our assessment, he is emphasizing employment rather than inflation, in an effort to prevent a major sell-off in the bond market before the recovery is firmly established. Growth is dollar negative because the bond market would turn into a bear market: foreigners’ love for U.S. Treasuries might wane, just as it historically often does during early and mid-phases of an economic upturn as the bond market is in a bear market.

- Good luck to Bernanke to raising rates in 15 minutes, as he promised he could do in a 60 Minutes interview. Sure he can, but because there’s so much leverage in the economy, any tightening would have an amplified effect. At best, we might get a rather volatile monetary policy. But we are promised by the Fed that this is not a concern for 2013.

- Both of these, however, suggest volatility will rise in the bond market. Remember what got the housing bubble to burst? An uptick in volatility. That’s because leveraged players, momentum players run for the hills when volatility picks up. And a lot of money has chased Treasuries, praised as the best investment for over two decades. We don’t need foreigners to sell their U.S. bonds for there to be a rude awakening in the bond market; we merely need a return to historic levels of volatility. Why is this relevant to a dollar discussion? Because a bond market selloff makes it more expensive for the U.S. to finance its deficits. Please see our recent analysis of the risks posed to the dollar by a bond market selloff for a more in-depth discussion on this topic.

Axel Merk is President and Chief Investment Officer, Merk Investments. Merk Investments, Manager of the Merk Funds.

Both the Federal Reserve and the Bank of Japan have gone all in with their attempts to revive weak, debt burdened economies with a pledge of unlimited money printing.

Both the Federal Reserve and the Bank of Japan have gone all in with their attempts to revive weak, debt burdened economies with a pledge of unlimited money printing.

After what appeared to be a coordinated effort by Europe and the U.S. to print their way to prosperity, Japan quickly joined the race to eternal QE with the

After what appeared to be a coordinated effort by Europe and the U.S. to print their way to prosperity, Japan quickly joined the race to eternal QE with the